We’ve claimed that Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) projects in this region will be critical to Metrorail ridership and sustainability. The good news is that our assertions are grounded in statistically rigorous evaluations of TOD’s impact on Metrorail ridership – here’s how. (Part one of a two-part series).

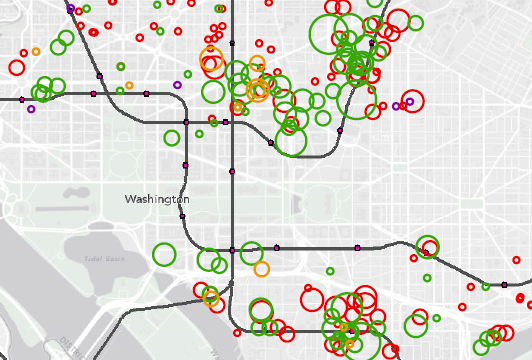

While factors like fares, service, and the economy can certainly explain some changes in Metrorail ridership, one absolutely fundamental explanation of differences in walk ridership between stations is development. Why does a station like Landover see only 50 riders arrive on foot each morning, and a station like Crystal City see over 3,000? Why does a station like Bethesda see balanced ridership in all directions, where a station like Suitland is almost entirely one-direction? Development. Even a simple scatter plot shows that households alone near the station explain 70% of AM Peak walk ridership!

Planning studies have long-posited that transit-oriented development is such a key part of driving ridership, and if that is the case, then TOD is vitally important to Metro’s long-term financial sustainability. We at Metro needed to quantify this link in a more sophisticated and system-specific way, and so we created a way to calculate the impact of land use changes (household growth, employment growth, new development) on ridership and revenue.

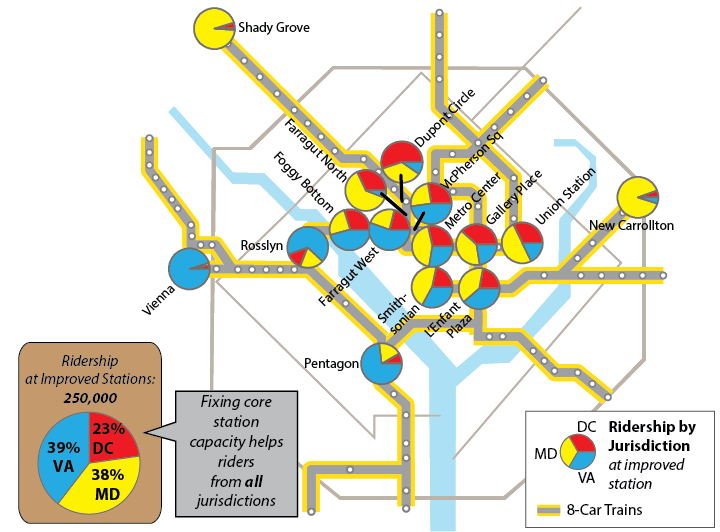

What is a Land Use-Ridership Model? To help, Metro’s Planning Office has built a Land Use-Ridership Model that will predict changes in Metrorail ridership as a result of occupancy changes (growth, decline, new development, etc.) in the station area. This model helps us get very specific when it comes to modeling the impact of land use changes on ridership and revenue. It helps us answer questions such as: “When developers build a new apartment building next to a Metrorail station how much ridership and revenue will Metro realize?”, and; “If an office building is proposed at one of four Metrorail stations, which location maximizes ridership and revenue without exacerbating core capacity constraints?”

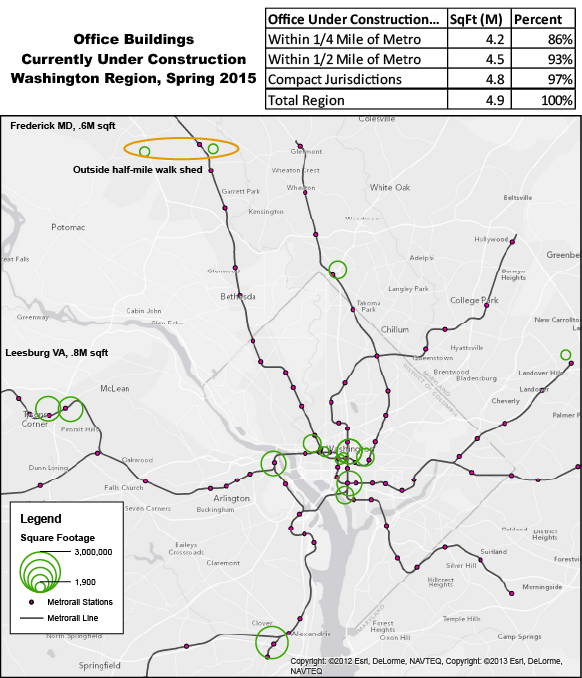

This tool is based on a rigorous understanding of the link between land use and the rail ridership we see today and is built on “direct ridership modeling techniques” found in academia. It also focuses specifically on “walk ridership” (which constitutes 38% and 78% of our AM and PM peak ridership), since rides related to bus transfers, parking, and other access modes are less related to adjacent land uses.

To build this, we analyzed the actual quantity of walkable land uses from each station area, assembled detailed information about land uses and densities in those areas (households, jobs by industry type), and also controlled for other, non-land-use factors that shape ridership – like network accessibility. In all we worked through over 200 independent variables in our modeling and also brought in experts from the University of Maryland’s Center for Smart Growth, professors Hiroyuki Iseki, Ph.D. and Chao Liu, Ph.D., to bring their analytical and statistical firepower to the fray.

How We Built It. We defined the walkable area as a half-mile walk along a road network, so we account for barriers like highways and fences. The half-mile cutoff is a bit longer than the median actual walk distance reported by our riders in the 2012 Metrorail Passenger Survey. For each station and its walk shed, we tested the following kinds of factors: Read more…

Recent Comments