Metrorail: A Long-Term Solution

Metrorail has had a huge impact on the region, but as we’ve seen with the Silver Line, it can take decades to get from concept to execution.

One of the questions I hear most often as a planner for Metro is When will a Metro station open in xyz neighborhood, “in Georgetown”, or “at BWI”? It was the first question at the March Citizens Association of Georgetown meeting. My response — “Decades” — often elicits audible groans.

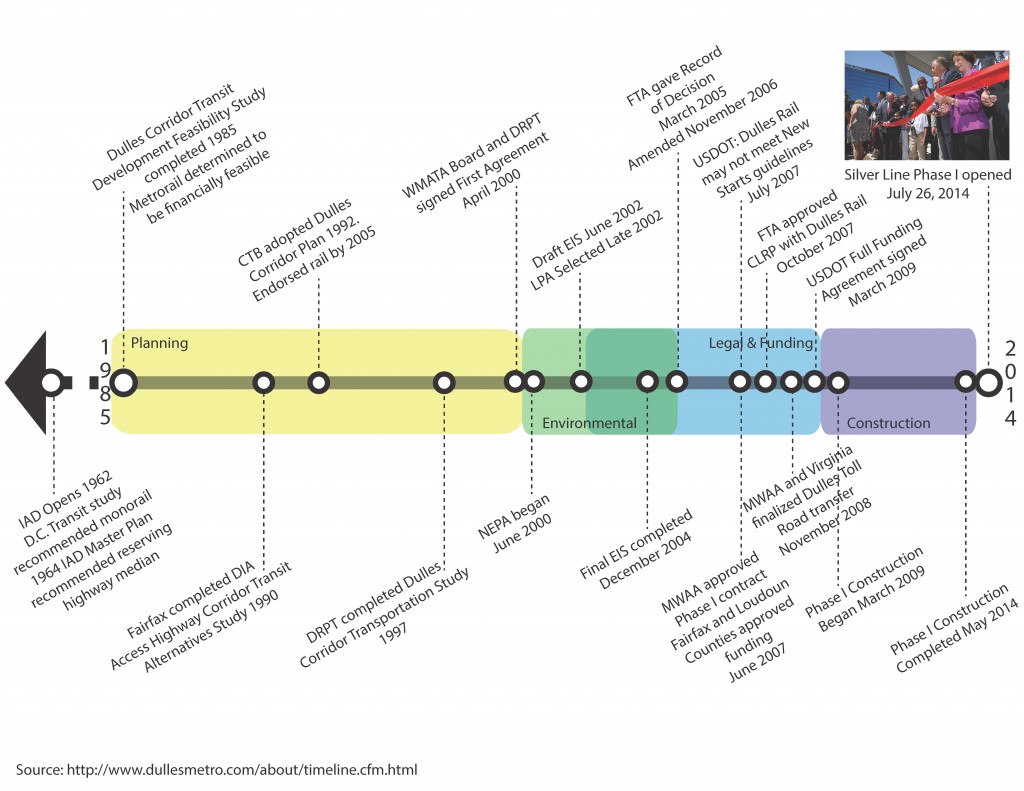

Given last summer’s opening of the Silver Line, we have a case study that can provide insight on how long it takes to plan, fund, and construct large infrastructure projects. The Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project has done a phenomenal job of maintaining a project timeline. Since the region has many recent newcomers, it is helpful to revisit many of the key milestones, as shown below. It is also helpful to remind readers that the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) was the ultimate developer of the Silver Line (both Phases I and II) and that the project “only” required cooperation among the Commonwealth of Virginia, MWAA, Metro, the federal government, and Fairfax and Loudoun Counties. While just one example, the Silver Line’s long story is not vastly different from other mega-projects happening in the region and across the country.

In summary it takes a long time to plan, gather support for, commit financing to, and construct a new Metrorail line, including:

- More than 15 years of planning and studying options;

- 6 years of environmental analysis;

- More than 3 years of legal and funding negotiations; and

- 5 years of construction

The region is vastly better off for the creation of Metrorail, and provided it’s planned effectively, the region needs more of it. However, expanding Metrorail cannot be a short-term transportation solution. The region’s residents, employers, and elected officials need to both support plans for the long-term, while also supporting improving today’s transit system. The short-term solutions include getting full funding for eight-car trains to increase Metrorail capacity, building more premium bus service on dedicated lanes like Metroway, finding other opportunities to prioritize transit on streets, making better decisions about where jobs and households are located, and/or bicycling and walking connections.

What, if anything, about the timeline is surprising to you? What opportunities do you see for us, as a region, to develop and get projects online faster? What are the challenges?

Everything in this country takes decades, if not generations, to build. Everything. NYC is still trying, after 90+ years, to get the 2nd Ave subway built. One small section will be open in a year or so, but for the rest…”funding uncertain.” Meanwhile, the 4/5/6 trains will remain at crush capacity for yet another generation.

Here in San Francisco, we’ve been trying to get Caltrain electrified for decades. Now that the new Transbay Transit Center is over budget, the extension of Caltrain (and electrification) from 4th/Townsend to the financial district has been pushed back at least another decade. BART is just now toying with the idea of having a second bay tube as part of it2 2050 plan. 2050! Bay Area traffic is second worst in the nation. Don’t expect any solutions in the next 20 or 30 years, I guess.

Meanwhile, other countries have their act together, be it mass transit projects or HSR. Heck, even Los Angeles is on the transit bandwagon.

I don’t doubt that it historically has taken decades to get new infrastructure projects from the planning to the operational stages. But… that’s a matter of choice on our part, to allow all these phases to drag on and on AND ON forever. Other developed countries manage to get new subways (and other big pieces of infrastructure) built within a decade or so… and no, they aren’t all dictatorships. Look at Vancouver for an example of a system operating in an environment very similar to the US, which managed to open the Canada Line in just 19 years of planning and construction. Spain, France and Germany all managed to open new lines in 10-20 years despite having thousands of years of pre-existing stuff in the way.

The main stumbling blocks seem to be:

(1) we can’t get our act together on the funding

(2) we can’t dedicate enough staff to the planning/environmental studies to get those done faster

(3) we can’t force local jurisdictions to cooperate with the goals of the greater region (usually in terms of routing decisions but also including station locations and decisions about tunneling vs using elevated tracks), which leads to much of the “legal” phase dragging on forever

But, we simply do not have the luxury of waiting 30-90 years anymore for building new transportation infrastructure, not with how our urban areas are growing. In another 30 years with no new transit lines opening, our cities will be totally gridlocked with cars and our economy (driven by the productivity in our cities) will tank.

If state DOTs can build interstate highways in less time, if the feds can create and mobilize entirely new bureaucracies like Homeland Security in less time… then there’s no reason, other than our inability to prioritize transit like we do roads and military adventures, why we can’t physically build new subways in less time, even while respecting the laws like ADA and environmental protection that make our construction take longer than in places like China.

It’s merely our choice: if American citizens/voters accept the presumption that transit construction cannot occur any faster, then American politicians will allow that presumption to become self-fulfilling.

It didn’t take 50 years to build the Wilson Bridge over the Potomac River. Several cities have built new streetcar lines in 5 to 10 years from the start of the planning stage. NYC’s extension of the No. 7 line to the Westside is taking less than 10 years. The general drawback for transit in the national capital region is the lack of substantial capital funding for capacity expansion projects.

@Patrick, I couldn’t agree with you more. It really comes down to a regional willingness to prioritize transit, a desire to fund it, and consistency between administrations (local or state) to make projects happen. I put this post together because I found it eye-opening as to how long each piece took. It isn’t something that most people have wrapped their heads around and it was in response to “how quickly can I get a stop in my neighborhood”.

@Steve, fwiw, the Wilson Bridge took 9 years to construct (or 13, if you count the Telegraph Road portion) – that doesn’t even include the planning, environmental, and funding timeframe. Again, the 7 Extension, started construction in 2007 and has yet to open. So really, it isn’t the construction part that tells the story. It’s the funding and regional commitment. Or lack thereof!

In that same time frame, the Chinese will build 20 new cities. I’m not saying that we should go to that extreme, but there has to be a happy medium here. Projects take far too long in this country.

Given the typical timelines that seem to be required to build transit lines now in this country, as exemplified by the Silver Line timeline shown above, we should be very, VERY thankful that much of the Metrorail system was built during the decades of the 1970s and 1980s. If we had not done so and instead waited to start building the Metrorail system until now, the cost would almost certainly be at least $40-$50 billion (in current dollars) and the construction timescale for the entire existing 129-mile system (including phase 2 of the Silver Line) would likely be measured in terms of centuries rather than decades.

It still amazes me to this day way the Metro Rail system was not taken way all the way out to Dulles international Airport when it was first planned, and would have been a lot less costly. At that time they already had international flights going to London and Paris. When you are planning large infrastructure transportation projects, you should be looking 25 to 30 years into the future, and at the demographic growth that is expected.Now because of that political short sightedness, this project has become much more expensive by a factor of at least 5 times more. And it doesn’t look like it’s going to get any better in the near future. Just look at the problem they are having getting the Purple Line going in Maryland. Look how long it has taken Metro to get the new 7000 series cars into the system. Then there’s the ill conceived idea about putting streetcars of the H St corridor in DC. Stayed tuned for more and/or less.

@Charles F Simmons

It was short-sighted to put Dulles out in the middle of nowhere. As a result, it would be a pain to get there even assuming frequent Metro service, and it’s one of the reasons it’s struggling now and losing so much business to National Airport – notwithstanding the massive population growth in NoVA.

You’re right, though, that our transit planning is plagued with a “think small, think only about the present” mindset. If this area ceases to thrive, THAT will be the primary reason.

@Anonypants

I think that can be said for many cities. Unnecessary excess of planning and bureaucracy coupled with short-term thinking and band-aid solutions supercede sound judgment and logic.

I lived in DC back in the 90s and then moved to San Francisco. I can tell you without hesitation that absolutely nothing gets done in the Bay Area that makes any kind of planning or transit sense. First, we have dozens of transit agencies that cannot effectively operate individually, much less coordinate with the other agencies. BART keeps building massive surburan commuter rail type stations, while the inner city cores are mass transit poor. SF MUNI is building a subway to nowhere, built purely to keep a whiny Chinatown pol quiet. The Caltrain extension to downtown is dead in the tracks after the funds were shifted to help pay for cost overruns on the Transbay Transit Center (now a $2B bus terminal, rather than a multi-modal station). In fact, the plan doesn’t even include a 1-block underground passageway from the TTC to existing BART/MUNI on Market St. Talk about not having one’s act together.

So how does this compare to building a new line in the Tokyo metro region? I’d be interested to see benchmarks against both public systems (like Tokyo Metro) and private systems (like JR, Keio, Tokyu). From the outside, so much of the planning process looks like it’s caught up in endless bureaucracy. That is a deliberate choice that we have made as a society. Transit systems don’t have to be owned by the government. Indeed, in Japan most of them are private companies. What would the plan, fund, build timeline look like under a different paradigm?

We are looking for solution for procurement of E&M systems comprising of track works, electrification power supply and catenary system, signaling system telecommunication system automatic fare collection platform screen door, lifts and escalators for MRT line.

Can you suggest few companies, who are expert in this?

Email : salman@dnsgroup.net

Overview: From start of environmental planning to opening day is less than five years.

From the mid-1980’s to the early 1990’s, the Orlando-Orange County Expressway Authority (OOCEA) was able to plan, design and construct freeway sections as toll roads in less than five years. The sections included toll plazas, interchanges and bridge structures. Initial total miles was 23, followed by 30 miles.

Background: In this timeframe, 600 new residents were daily arriving in Central Florida. Former orange groves would be converted to new development in less than a year. Transportation corridors were closing by such development.

Here are the pertinent factors of this agile, aggressive program:

– Systems planning was complete. Environmental planning with general engineering was one year; final design with right-of-way documents was one year; right-of-way acquisition, which overlapped final design, was three-quarters year; construction with commissioning was two years.

– Funding was through OOCEA bond issues that were based on toll revenue of operating sections. In other words, funding had no Federal or state sources.

– Thus, there were no Federal mandates or review processes. The spirit of Federal law, rules and regulations were, however, recognized in the implementation of the toll road expansion program.

– The majority of the OOCEA Board members were appointed by the Governor. Orange County Board chair and Florida DOT District director were also members. Thus, the Board could be aggressive.

– The OOCEA staff was small, having an Executive Director, Director of Planning, Director of Engineering, Director of Construction and Director of Finance. There was reliance on consultants for planning, design, design review, right-of-way acquisition, and construction management. Important decisions by the OOCEA staff could be made in less than an hour.

– OOCEA engaged the leading environmental interest parties as an advisory group, including Florida Audubon Society, Orange County Audubon Society, Sierra Club, Friends of the Wekiva River, and Friends of the Econ River.

– There was political will and support by the general political and business communities.