Mass Transit Needs Mass

Transit expansion is in demand but Metrorail, light rail, and other high capacity transit projects can be expensive to build, operate and maintain. With limited resources to invest, our region must ensure that these projects serve the most robust transit markets and are supported by strong transit friendly policies.

Informed by our peers and local performance measures, Metro is developing guidelines that the region can use to inform development of high capacity transit projects. As we’ve explored previously, there’s much more to transit expansion than Metrorail. In fact, due to the cost associated with Metrorail expansion along with existing land uses and built environment in much of the region, most of our future high capacity transit projects will be made up of other transit modes. But what is the best way to decide what mode best fits each corridor? The goal of the expansion guidelines is to inform those decisions.

Development in Arlington’s Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor has validated initial and ongoing investments in Metrorail. (source: Arlington County)

A literature and peer review included policy documents from BART (PDF), the Bay Area Metropolitan Transportation Commission, Florida DOT, Virginia DRPT, Federal Transit Administration (PDF), and research from the University of California Transportation Center (UCTC). The review found that ridership, density, the presence of walkable streets and sidewalks, local plans and policies, and cost effectiveness are the most relevant criteria to evaluate transit projects and that rigorous performance targets are needed to support each transit mode.

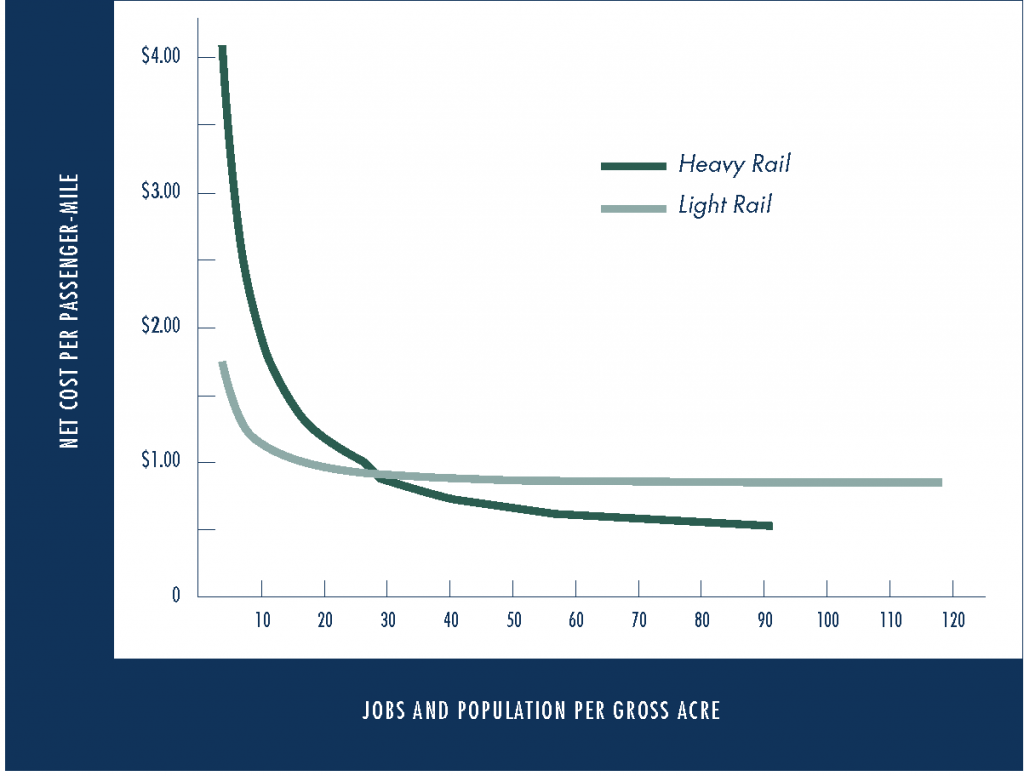

Net cost per passenger mile by density in average heavy and light rail cities. (source: Access Magazine #40, UCTC.)

For example, the highest capacity and most expensive modes like Metrorail (i.e., heavy rail), are most effectively supported by higher density development so that the up front capital costs and ongoing operating and maintenance costs are financially sustainable. UCTC’s research (graphic above) found that on average only at 30 combined jobs and people per acre across all stations does heavy rail begin to become more cost effective than light rail. Furthermore, the researchers found that transit lines connecting large job centers were more successful in boosting ridership than those that relied more heavily on connecting households.

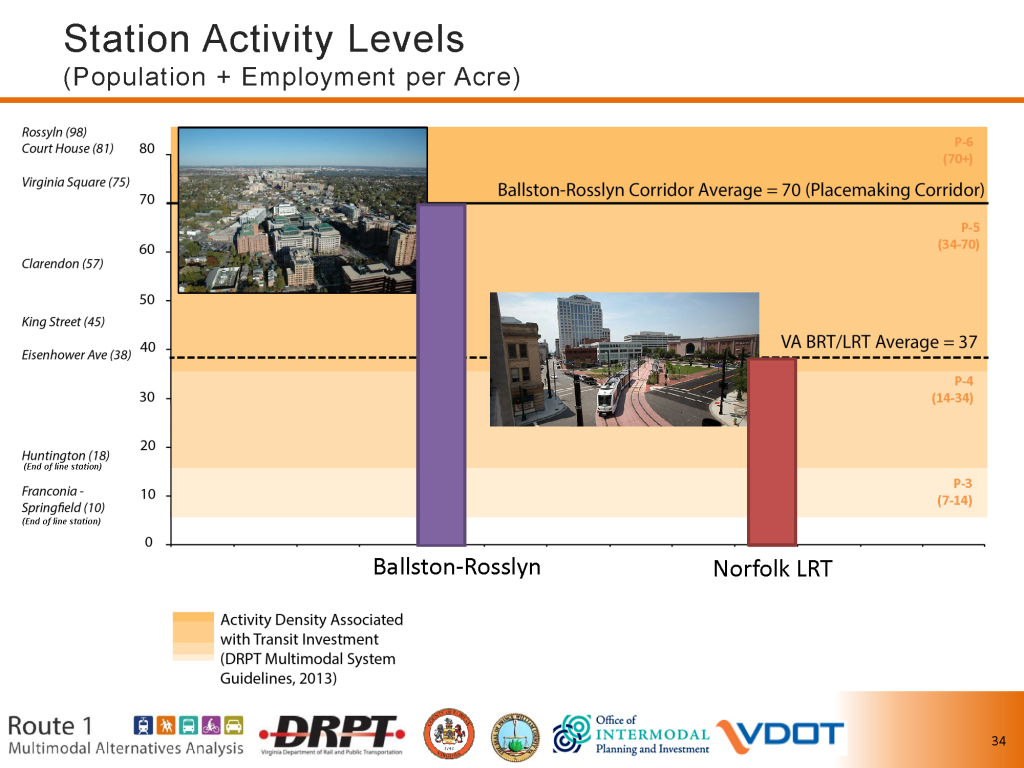

Fortunately, some of our regional partners have already identified these issues. Stakeholders in the Route 1 corridor study in Virginia are now weighing the development and public investment tradeoffs of bus rapid transit and light rail as alternatives to extending the Yellow Line in that corridor.

Over the coming months, we will be developing and finalizing our guidelines for major transit modes so that they can be used as a resource to guide regional and local transit investment decisions.

How many of Metro’s current extensions, lines, and stations actually meet that 30 jobs/people per acre figure?

Actually, you can see some of the VA station density values in the bottom graphic. I do not have a comprehensive list, but many stations are above the 30/acre value, although certainly there are plenty that aren’t. For example just as we might expect all of the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor stations are at or above 60, while all of the Blue Line stations in Prince Georges County are well below 30.

Clearly, population and job density around heavy rail (i.e., Metrorail) stations is important, and the more the better. But let’s also remember that the desired average of 30 or more combined jobs and people per acre (within a half mile of the station) should apply across all stations of any proposed extension rather than for every station individually. And that means that some stations could make up any deficiency below the 30 jobs/population per-acre average by having a substantial amount of auto (and bike) parking and bus feeder services.

This is precisely the situation at Metro’s Franconia/Springfield station, as was cited in the University of California Transportation Center research referenced above: “Transit-supportive density thresholds need to be viewed with caution. There is no one hard and fast rule that can be applied across all projects. Regression-based models mask considerable variation. For example, despite low surrounding densities, the Franconia-Springfield extension of the Blue Line in Washington, DC, is one of the best performing investments. Low capital costs, a plentiful supply of parking at stations, frequent train service, and good access to downtown jobs contribute to low costs per rider. By contrast, the Buffalo light-rail system is one of the least cost-effective, despite above-average job and population densities.”

Thus, some stations on a proposed extension will likely meet or exceed the jobs/population threshold without a significant amount of parking while others will require more parking and bus feeder services to be viable. But both types of station situations are often needed to take a meaningful amount of cars off the road and reduce congestion at least a bit. And beyond that, where do other types of activities around stations (retail like at Tysons Corner or Pentagon City, higher education like the GMU campus at Virginia Square, or hotels like the new Hyatt Regency at Tysons Corner) fit into the calculations of the viability of a proposed station?

As for densities along the Route 1 corridor, the corridor analysis so far seems to understate the potential for development and parking at several potential station sites south of Hybla Valley, and it almost totally ignores the potential impact on transit ridership of the more than 50,000 people that are currently stationed or working at Fort Belvoir. That’s why I’m really disappointed that a Yellow Line extension from Huntington all the way to Fort Belvoir wasn’t included as one of the options that received detailed analysis in the corridor study. Even if it wasn’t viable, it would be nice to know the assumptions used as well as why such an option fared worse in comparison to the other options.

And speaking of density for heavy rail, isn’t there sufficient current and planned density in Fairfax County at Skyline and Mark Plaza (especially with the massive new DOD building) and potential density upgrades along Columbia Pike in Arlington to warrant a Metrorail extension in that corridor instead of the planned streetcar? I believe a streetcar is the wrong mode, particularly in mixed traffic, in a relatively dense corridor radiating out from the region’s core and will fail miserably in terms of both passenger carrying capability (given the lack of a dedicated ROW) and economic development. Although more expensive, a Metro line would undoubtedly be much more beneficial to accomplish both tasks, as has been proven in other corridors.

And finally, like “Low Headways”, I also would like to know how many current stations meet the 30 jobs/people per acre average. Perhaps more interestingly, how many stations met that figure in 1969 when Metro construction began? I would expect that 1969 number to be pretty small, even along the currently-much-touted Rosslyn-Ballston corridor, with probably no stations qualifying in Alexandria, Fairfax County or Prince Georges County, and only two (Silver Spring and Bethesda) even being close in Montgomery County. In short, if the current FTA rules had been applicable in 1969, we very likely would not have a Metro system today that, for all of its faults, is indispensable to reasonable mobility in the Washington area.

OK, I suppose that’s enough for one post. :-)

Mike, you are correct about the 30 threshold. Hopefully I made it clear that it’s the average across all stations, not every station. I too noted the Franconia-Springfield extension in the UCTC research and the point made about cost effectiveness. There are more ways to achieve ridership than density alone, however costs are a big variable and there are impacts to achieving ridership primarily through park and ride. With the exception of the recession, construction costs have risen faster than general inflation, making the return on investment more challenging for large capital projects like a Metrorail extension. Also, although they can be useful for expanding access beyond the walkshed, park and ride lots tend to produce a lot of peak ridership, usually with very little off-peak demand. This disproportionally drives operating costs upward through split operator shifts, peak fleet, storage and maintenance requirements, increased support costs, and park and ride facility maintenance costs. Park and ride lots also don’t generate tax revenue to the local jurisdiction (that can be directed to support transit operations), increase peak crowding, and so forth. By contrast, stations with higher densities and a mix of uses such as Ballston, Columbia Heights, Bethesda, and Silver Spring produce more sustained demand throughout the day which creates positive benefits for transit through off-peak demand and generates substantial tax revenue to the local jurisdiction.

I can’t speak directly to the specifics of your questions about route 1, but the study team has done a good job of laying out the tradeoffs of a possible investment in Metrorail in terms of the type of growth that may be needed. In some cases, levels of growth needed to support Metrorail are either not desired by the community or simply not economically viable over any reasonable timeframe. I suggest reviewing the study website or contacting their team for more details. I also can’t speak to the densities along Columbia Pike, and would refer you to Arlington County as to whether they considered Metrorail in their corridor studies.

Again, I don’t have all the values for every station, but will be able to provide values for a selected number of stations in a future post. I’d argue the stations that would have met this current target in 1969 isn’t really the relevant question. Perhaps the better question would be what stations would have met relevant land use targets of the time for a future “design year” such as 1990. It’s possible that the land use targets in 1969 would have been lower simply because the costs were many times lower to build and operate heavy rail at the time as opposed to now. But all things considered, I’d agree we are pretty fortunate to have the system we do today.

Agreed about Columbia Pike…should be Metrorail, not streetcar. Streetcars only have high performance when they have separated ROW. The H Street streetcar system will turn out to be even slower than the bus. Wait and see.

Another issue with Metro planning is the neglect of suburban-to-suburban commutes (I use the terms suburban loosely…basically VA-MD connections). Working with an existing hub and spoke system has its challenges, but Metro should consider investment in making travel between MD and VA easier and faster.

Park-and-ride stations are not the final state of the urbanized environment that transit makes possible, but they are useful in the D.C. area’s current situation as steps toward that environment. And they were much more useful, indeed essential, in Metro’s earlier years.

If you want to get rid of parking lots & above-ground garages (and you do), it’s a much higher priority to eliminate them downtown than at Franconia, Vienna, or Shady Grove. The parking at the end-of-line stations made possible the transformation of downtown DC that has largely eliminated above-ground parking. Without park-and-ride, you would still need parking for all of the downtown workers who don’t live in walking distance of Metro and can’t or won’t take the bus to the station.

Now we’re seeing development on parking lots at White Flint and hopefully soon Greenbelt, Takoma, etc. But that’s now. When there were lots of parking lots downtown, it made more economic & planning sense to build on downtown parking lots than to build on parking lots far from downtown.

JONATHAN METRO NEED TO FOLLOWED LIKE NEW YORK CITY TRANSIT DID.WASHINGTON DC WMATA METRO NEEDS TO REBUILD DC TRANSIT,WMA,AB&W WVM,AND PUT THE SIGN METROBUS OVER IT.AND USED THEM AGAIN