Shared Mobility – Complementing Public Transit in the Nation’s Capital

In the DC region, shared mobility (Uber, Lyft, etc.) are actually complementary to the transit network. Here’s why we see opportunities to consider even better system integration.

“Transportation Network Companies” – you know them as Uber, Lyft and a host of other brands – are now part of the urban transportation landscape. Some have suggested that the rise of their popularity contributes to ridership decline on Metrorail and still others have heralded their emergence as the end of transit as we know it. Always focused on investigating trends and proliferating fact rather than folklore, we wanted to know the truth. Should Metro be nervous? Are customized trips like these going to put traditional bus and rail out of business?

Unlikely.

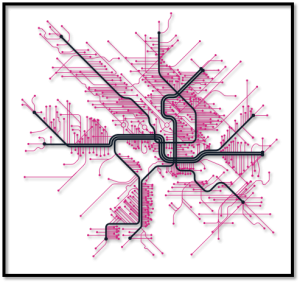

Research (PDF) published by the American Public Transit Association and Transportation Research Board – and which I had the pleasure of helping to oversee – tells us that customers of ridesourcing tend to use the services when transit is less available as well as to get to destinations not easily served by traditional transit. Furthermore, we learned that in the DC region especially, these TNCs tend to function as informal “Metrorail shuttles” – almost two thirds of Uber trips in the District begin or end at a Metrorail station, and slightly more than a third of Uber trips follow that pattern when we zoom out to the entire region. Similar statistics prevail when examining the usage of car sharing companies such as Zipcar and Enterprise. Finally, the data indicates that 57% of frequent users of ridesourcing companies as well as car- and bike-sharing customers identified bus and rail transit as their preferred transportation mode. This tells us that these services have an important role in complementing the Metro rail system for many customers.

We asked our customers about their TNC usage to get a more granular (and first-person) perspective on this issue. A survey of Metrorail customers indicate that they tend to use the services of ridesourcing companies for late-night entertainment transportation and during the off-peak when Metrorail operates less frequent service. This comports well with data from DC TNCs about their overall trip demand profile, which shows sharp spikes during the midnight to 3am period even in the months prior to the curtailment of late-night weekend Metrorail service.

The value of partnerships with transit providers is increasingly clear to the ridesourcing industry. For example, Lyft launched their own marketing campaign in 2015 designed to attract customers to their services as a means of providing access to the Metrorail network. Many of our peer transit agencies are engaging in partnerships with ridesourcing companies and taxis to facilitate better and more seamless transit access and tripmaking as well as reduce operating costs associated with serving limited markets by bus. Lyft and Uber are working with a number of transit agencies around the country to market and provide access to their services. For example, DART and MARTA include links to Uber and Lyft on their trip planning apps, and COTA in Columbus, Ohio and MARTA in Atlanta are exploring programs to subsidize some trips to provide equity of access to those outside the reach of their traditional bus and rail services, particularly areas that would costly to serve with bus and rail service expansions. Many more partnerships are coming to fruition in small and large communities alike.

We’ve taken a stab at highlighting some of the ways that we believe these services could continue to be better integrated into the regional mobility network, with a specific focus on Metro. In light of what you’ve experienced as a rider of Metro and other service providers in the region, what opportunities do you see for Metro to engage in the shared mobility economy?

Download our draft white paper: TNCs and WMATA: Considerations for New Tools, Opportunities, and Partnerships (PDF)

Interesting numbers here. Still reading over the white paper, but does WMATA have an answer for commuters who typically ride Metrorail, but on particularly “bad” days resort to hailing a ride from their Metro station to their final destination? Anecdotally from what I’ve observed, this seems like a sizable problem not only when there are particularly significant delays in the system, but also when there are perceived delays due to things like crowded platforms. I’m curious what you think WMATA could potentially do to encourage these folks not to leave the platform for another service once they arrive.

Good comments and questions, James. I’m sure you are aware, but starting July 1 WMATA offers a grace period for those that enter a station and decide, based on observed conditions, whether they need to choose an alternate mode of transportation. The thinking is that customers have choices when they come to mobility, and if they believe that a better option is to try to hail a rideshare or bike or walk, we owe it to them to allow them to make that decision quickly without feeling the pain of cost incurred for a trip not taken.

This is an interesting relationship between transportation services. I remember when Lyft ads started appearing on Metro, riders were confused (on twitter) why Metro would allow this from their ‘competition’. But to be fair, at that point the ads didn’t show Lyft as a complementary service – Though it was being used as one.

Now, with the 15-minute grace period, it will be interesting to see how many more riders decide to step away from Metro and into a Lyft / Uber when confronted with delays.

@Sam Winward

Many of us (present company included) have done as such, and the GM’s goal is to make sure that folks can take advantage of these options when necessary.

Urban mobility is an interwoven fabric of many options – walking, biking, transit, and now carshare/bikeshare/ride-hailing. A city that provides lots of ways to get around is better poised for productivity and global competitiveness.

I’m not sure I understand what is meant by the claim that “two thirds of Uber trips in the District begin or end at a Metrorail station, and slightly more than a third of Uber trips follow that pattern when we zoom out to the entire region.” The implication seems to be that those Uber trips are links in a chained trip that includes transit, but do you have survey or other data indicating that those passengers actually got on or off a Metrorail train? Isn’t it possible that simply because there are lots of destinations clustered around Metro stations, the passenger could have been accessing one of those destinations “at” a station without interacting with the transit system at all?

@Dan

Excellent comment, Dan. To be clear, we don’t have the type of data that would allow us to directly link an Uber trip to a Metrorail trip. And by no means would we suggest that 100% of these trips feed into/out of Metrorail.

However, the ride hailing platform for Uber does a few things which can help provide depth to the potential relationship. When specifying a pick-up location, the app will use the GPS from your mobile device and identify a pick-up location( e.g. rather than “Dupont Circle”, it will direct you to 1736 DeSales Street”) So we know that for origin pick ups, the customer would have to override the default GPS pickup to specify a Metrorail station.

On the destination side of the trip, things get dicey. Folks can often use a geographic identifier such as a Metrorail station and then go from there. Or they can plug in the actual address for curb-to-curb service. What % does the former and what % the latter? We don’t have any data on that and the work that I helped oversee at TRB did make sure to keep proprietary data proprietary. However, given the nature of the service, customers who have the option of plugging in their actual destination rather than a landmark (such as a Metrorail station) might be inclined to do so (why get out of the car and walk around a few blocks when you’ve almost bought those last few blocks of travel?).

No indisputable answer, to be sure, but some directionality to be sure and enough information to at least warrant digging deeper.

At the regional level, the figure becomes more meaningful, because there are fewer Metrorail stations that in and of themselves serve as reasonable origin/destination points – unless one was riding the system.

We’ll have to keep watching this as more information becomes available, for sure.