Solving the Region’s Congestion Woes – One Step at a Time (Part 2 of 3)

Improving pedestrian connectivity takes cars off the road at a formidable clip – rivaling the power of all of the region’s planned roadway additions and “last mile” transit connections. Cheaply and quickly.

This post is part two of a three-part series.

The data is finally in, and we now know that walkable station areas result in fewer motorized trips, fewer miles driven, fewer cars owned, and fewer hours spent traveling. And when we improve the pedestrian and bicycle access and connectivity to Metrorail station areas, ridership goes up, putting a major dent in congestion by taking trips off the roadways. Earlier, we discussed what it means to build walkable station areas and research shows the tremendous benefits to the region of making this a priority.

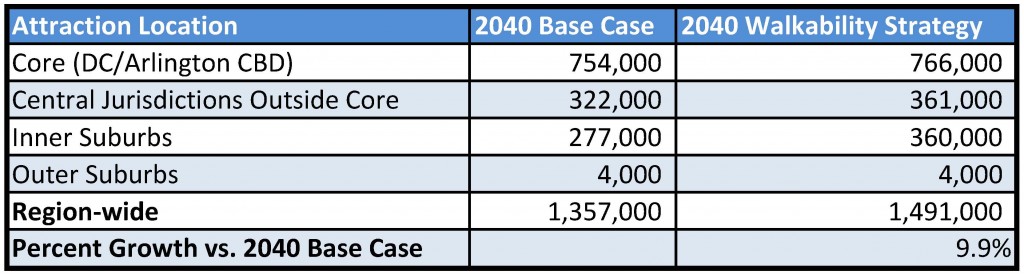

First, our data confirms that when walking access to transit is improved, transit ridership goes up – way up. In the 2040 Regional Transit System Plan (RTSP), we stress tested TPB’s transportation model to improve walkability to the transit network and saw huge increases in transit linked trips. These trips go up by about 10% region-wide and we get an increase in transit mode share for all regional trips by 0.5%. That’s over and above the roughly one percent increase in mode share we anticipate occurring as a result of building the entirety of the CLRP, an impact about half that of constructing all of that transit.

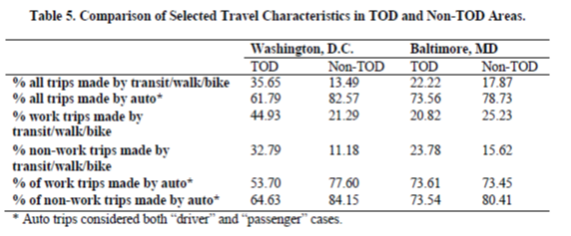

Second, our RTSP modeling probably understates the opportunity. In a relatively unheralded study published by Maryland’s State Highway Administration, researchers proved that in areas within a half-mile of transit stations (the study defined TOD areas as those within ½ mile of a fixed-route transit station), the percentage of transit/walk/bike trips is three times higher than in non-TOD areas – totaling more than 1/3 of ALL trips. When we look at work trips that figure climbs to nearly 50%, and the households in these TOD zones were four times more likely to be zero-car households (almost 20 %).

Source: Development of a Framework for Transit-Oriented

Development (TOD), December 2013. Click image for PDF.

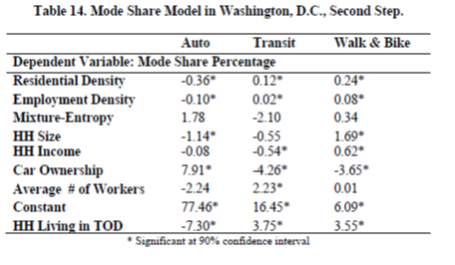

Perhaps most intriguing – the research shows that for every 100 units of residential units added to a TOD area, transit mode share goes up by 1.2% Assuming that all of this pedestrian activity is using a pedestrian network – formal or informal – this tells us that the walkable infrastructure that should accompany density is hugely important to getting cars off the road.

Source: Development of a Framework for Transit-Oriented

Development (TOD), December 2013. Click image for PDF.

Why pay attention to all of this wonkiness? The simple reason is that all of this information tells us improving pedestrian connectivity takes cars off the road at a formidable clip – rivaling the power of all of the region’s planned roadway additions and “last mile” transit connections. Cheaply and quickly.

Can the region afford to ignore this high-impact cost-effective mobility solution that can be implemented right now?

If we know that the most potent means to reduce auto trips is to: 1) squeeze every drop of capacity out of the existing transit network; 2) enhance or construct pedestrian connections to transit; and 3) increase residential and office densities at or near transit, then we need to consider funding Metro 2025 and making every station area walkable. The cost of a comprehensive walkability strategy is infinitesimal compared to the cost of hundreds of billions of dollars in last-mile solutions and freeway expansion.

Certainly weighing the costs and benefits of approaching our transportation dilemma by pursuing land use and accessibility improvements is worth evaluating, especially in comparison to trying to build our way out of the problem alone. What do you think?

Increasing affordable development (residential & commercial) near Metro is the key. Unfortunately, Metrorail’s attractiveness encourages land speculation that inflates land prices. This pushes affordable development to cheaper, but more remote sites.

Communities can remedy this by reducing the tax rate on privately-created building values and increasing the tax rate on publicly-created land values. The lower tax on buildings makes them cheaper to build, improve and maintain. This is good for residents and businesses alike. The higher tax on land discourages speculation, keeping land prices low.

For more info, see “Using Value Capture to Finance Infrastructure and Encourage Compact Development” at https://www.mwcog.org/uploads/committee-documents/k15fVl1f20080424150651.pdf

@Rick Rybeck

That may be the case, Rick, and I believe we see this in “favored quarter” portions of the D.C. Metro Area. I encourage the readers to remember that Metro does not develop housing, and that when the Real Estate office engages in development, it does so within the confines of local zoning, permitting, and development ordinances.

I wonder if anyone has done an analysis of how much of the existing housing stock within one-half mile of each of Metrorail’s station areas is affordable to 60%, 80%, 100%, or 120% of AMI. If that exists, it would be an important body of data.

After looking over a few of tthe blog posts on your web site, I truly like your technique of writing a blog.

I book-marked it to my bookmark site list aand will be checking

back in the near future. Take a look at my website too and let me know your opinion.

@Shyam

@Shyam,

Sorry to be slow responding. I believe that MWCOG (as part of their TLC program) reviewed the supply of (and threats to) affordable housing near existing Metrorail stations. However, I don’t recall that their study came up with any recommendations for dealing with the loss of affordable housing near Metro. As you pointed out, Metro controls only a tiny fraction of land that benefits from its transit service. It is really the responsibility of the surrounding jurisdictions to create the right rules and send the right signals to the private sector to maximize the amount and affordability of housing that is built nearby. There is no single magic bullet. But by allowing private landowners to obtain windfall profits from proximity to Metro, we are fueling the engine of land speculation — a parasitic activity that diminishes affordability and leads to the real estate boom and bust cycles that periodically bring our economy to its knees.